Boutique Builder

Self-made, successful developer/home builders usually start very small and if they survive in a tough business, may well eventually build hundreds or even thousands of homes and condo units a year in the Greater Toronto Area. Walter Harhay is doing it in reverse order.

He started really big – building billions of dollars worth of dams, bridges, tunnels, highways, water and sewage infrastructure, factories, office and residential high-rise buildings across Canada during his 17-year career with the former Pitts Engineering Construction Ltd.

Pitts was one of several predecessor companies that have morphed into Toronto-based Aecon Group Inc., Canada's largest publicly traded construction and infrastructure development enterprise.

Mr. Harhay, a civil engineer, did some post-Pitts morphing himself about four years ago when he started Harhay Construction Management Ltd. He's the president, although that's not especially grandiose, given he has four employees with whom he has a long professional acquaintance. "I might have stayed in the heavy construction field as a general contractor after Pitts, but didn't have that kind of capital to invest for equipment, so I went into construction management instead," Mr. Harhay explains.

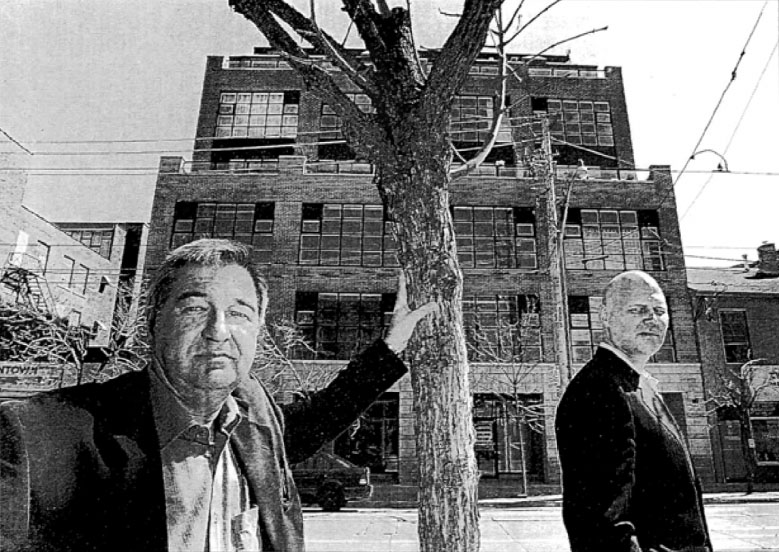

He was in fact starting to manage the construction of Tecumseh Lofts at King Street West in downtown Toronto when the owner decided he didn't want to carry on alone. Mr. Harhay bought into it as a partner and at that point turned into a small condo developer who is also, needless to say, his own general contractor. That's unusual because most condo developers hire general contractors, except for the few largest developers, who have in-house construction arms.

Mr. Harhay has so far concentrated on new condo lofts, except for Tecumseh, where he added four floors on top of the renovated single-storey original building to create a total of 28 units. He has also stuck to the downtown's oldest neighbourhoods along King Street West, although not slavishly so.

Brad Lamb, one of the city's busiest condo marketer/brokers – he expects his firm will sell about 1,400 units this year – sells Mr. Harhay's projects, and recalls that the Tecumseh and 30-unit Abbey Lane Lofts were snapped up during the earliest stages of construction.

The third project – Stewart Lofts, a 47-unit condo in the same general neighbourhood – only had two units left in early April and the shovel hasn't even gouged the ground. Whoever buys a unit on the ninth floor will never know there is a private swimming pool on the 10th-floor penthouse. After all, what is a swimming pool compared with the dam for a $250-million hydro-electric power construction project in northern Manitoba that Mr. Harhay managed years ago?

Mr. Lamb, who has a small financial interest in a site Mr. Harhay bought recently at John and Queen Streets for a 46-suite condo, says 18 of those units were sold on the strength of some recent, modest press coverage.

It obviously takes much less sales effort to sell 46 condo units than 460 units. Still, there appears to be a market awaiting Mr. Harhay's kind of product – modern condos with a traditional industrial loft conversion flavour in the theatre/entertainment and central financial districts.

"Walter is the only one in town doing little boutique buildings," Mr. Lamb says, "with minimum 10-feet ceilings, which can go to 11 feet. Usually eight feet is standard and nine feet is amazing." Mr. Harhay said he wasn't easily persuaded to build 10-foot ceilings, because "that last two feet is all cost, although our clients can see added value in that."

They're also a good investment, because Mr. Lamb says the original owners in Tecumseh Lofts, for example, have seen the $180,000 they paid for a unit appreciate to $300,000 and sell within days. If there was anything for sale at Abbey Lane Lofts, owners could get 40 per cent more than they paid for a unit two years ago, which Mr. Lamb says far exceeds the increase in the general condo market. But the owners aren't selling.

Mr. Harhay puts more of an understated civil-engineer, construction-project-manager spin on his projects: "We sell concrete, steel, wood and glass, the architects come up with creative designs and we do the construction. We also get funding for these projects because investors feel more comfortable with a contractor who knows what he's doing."

Mr. Lamb is, coincidentally, a professional engineer by training, so he and Mr. Harhay share a technical and problem-solving mindset. Mr. Harhay says his engineering background is relevant to building condos, which he describes as a "form of heavy civil construction which requires a lot of technical expertise, compared with building houses."

Would they do one of those warehouse conversions? The right building would have to come along, says Mr. Harhay, although Mr. Lamb suggests the factory lofts business in Toronto is basically over because all but about six industrial buildings downtown have been converted for office and other commercial purposes.

Mr. Lamb says he shares Mr. Harhay's need to feel proud of their projects. In fact, he says he could take on about 50 projects a year to promote and sell, but will only do half that number because too many condos in Toronto represent "bad planning, terrible architecture, too many different finishes. About 75 per cent of them should never have been built."

Should the city's planning department have anything to say about that? "The planning department appreciates great architecture, but doesn't have the stick to hit you with to force you to do it. Nor do they care much about materials and how a building looks," Mr. Lamb says.

And developers? "They don't understand why one architectural design is so much better than another. It isn't what they've done before and may not be to their taste. Walter actually wants to do good projects," he continued, as does Toronto-based Context Development Inc., most of whose projects his firm has represented.

Apart from the pleasure of producing something architecturally worthwhile, he says the difference between good design and schlock shows up in what resale units fetch and how long they sit on the market.

As for the career change relatively late in life (he's 57), Mr. Harhay says he likes living in Toronto and doesn't miss getting up at 6 a.m. when he worked for Pitts in Edmonton. He lives in the suburbs with his wife on, presumably, a large lot, because he says he "like lots of grass, although I don't like cutting it."

Does that mean they may some day move into a downtown condo? "I'm basically a suburban type, but yes," he says, "I could see us eventually going into a condo."